Allopathic physicians, those that practice “conventional” medicine, use vocabulary and special terminology to identify conditions happening within the body, their causes, tests, and treatments. These include terms like mastitis, heart attack, cystic fibrosis, mastectomy, complete blood count (CBC), high cholesterol, etc. Towards the end of the 20th century, many Americans began to understand the allopathic terminology used by their physicians. Patients now have access to a number of print and online resources like the Merck Manual, MedlinePlus, WebMD, the Mayo Clinic website, and many more. This well of easily accessible knowledge has empowered many patients to proactively partner with their medical providers to improve their health through diet, exercise, prescription medicine, integrative medicine, and surgery when necessary.

Like allopathic physicians, Chinese medical practitioners have their own terminology when working with and treating patients. Oftentimes, patients are less knowledgeable about the terms or lack a deeper understanding of the definitions. Sometimes misunderstandings occur when patients attempt to frame their practitioners’ statements in a western medical context. Although there may be some overlap in describing a medical condition between Chinese medicine and allopathic medicine, the terminology of the two professions is completely separate and quite different. With this in mind, here is a review of some “lingo” that may help patients better understand Chinese Medicine and how to partner more effectively with their acupuncturist or other practitioners in non-traditional medicine.

Defining Qi: The Life Force and Foundation of Chinese Medicine

The concept of Qi is the foundation of Taoist practice and Chinese medicine. Searching the internet for the definition of “qi” produces several meanings including an ethereal substance, breath, vital substance, energy, etc. However, these definitions have little meaning without an understanding of Chinese philosophy and medicine. Qi cannot be measured by current scientific methods, and for this reason, it may be difficult for some people to either interpret or visualize.

One literal translation of the Chinese character “qi” is air or breath. However, Qi is more than just a person’s air or breath—it is their vitality. Therefore, a good working definition in terms of Chinese medicine is “life force.” This concept of life force has roots in other cultures as well such as prana in Hindu philosophy, mana in Polynesian mythology, and pneuma in Greek mythology.

In Chinese medicine, Qi is one of the vital substances of the human body. Our bodies are dependent on Qi to walk, move our arms, digest food, breath, pump blood, chew, urinate, etc. Therefore, an obstruction or blockage to the normal flow of Qi can create pain or illness. Qi is considered to be one of the fabrics that make up life even though it cannot not be seen or scientifically measured. Practitioners of Chinese Medicine are primarily looking to balance and remedy the different ways in which Qi can be compromised such as stagnant, deficient, rebellious, or sinking.

Qi Stagnation

One of the most common pathologies seen in America is Qi stagnation, which is defined as life force that is not circulating throughout the body because it has become stuck. Characteristics of Qi stagnation include pain, irritability, mood swings, sighing, depression, bloating, among others. The etiology of Qi stagnation is most often unexpressed emotions. However, there may be other causes such as physical trauma.

Qi Deficiency

Qi deficiency is also quite common in America. It is a condition in which the body does not have enough life force to continue healthy body functions at a person’s current level of activity. Tiredness, loose stools, weak voice, breathlessness, reduced appetite, and several other symptoms are characteristic of Qi deficiency. It can be caused by poor diet, old age, illness, over taxation of the body, and genetic disposition.

Rebellious Qi

Rebellious Qi is defined as life force that is moving in the opposite direction than it should. It can affect any of the twelve meridians or organ systems. Symptoms of Rebellious Qi may include vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, burning urination, coughing, asthma, insomnia, irritability, mental restlessness, and many others. Rebellious Qi is disruptive to the system and is considered to be a more severe form of Qi stagnation. To provide an analogy, if a water drainage pipe becomes clogged and it is not resolved, eventually, the pipe will back up into the sink, tub, or toilet. This back up would be considered rebellious Qi because fluids are moving in the opposite direction than normal.

Sinking Qi

Sinking Qi is a more severe form of Qi deficiency. If Qi becomes severely depleted, the life force will be unable to hold other vital substances or organs in their proper place. Most often, this depletion of Qi may result in prolapsed organs. Symptoms of sinking Qi include fatigue, depression, lethargy, bearing down sensation, as well as prolapsed organs. Sinking Qi has the same causes as Qi deficiency, but the causes (poor diet, illness, old age, weak constitution) have continued for a much longer period of time without correction.

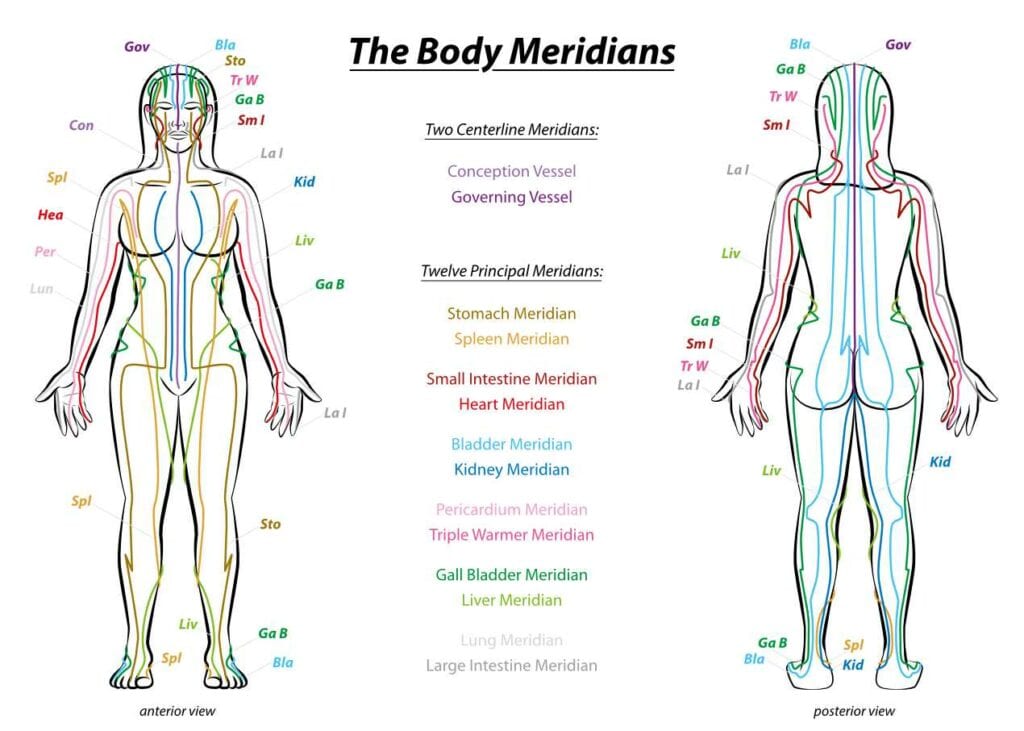

Defining Acupuncture Meridians: The Pathways for Qi

In Chinese medicine, the meridians are the pathways through which the Qi flows. One might compare them to blood vessels, but they are quite different from arteries and veins. Some would say the body’s meridian system is like a network of streams and rivers. Just as water flows in one direction from one stream to another source of water, Qi flows through one meridian to the next. Meridians are separate, yet connected. There are several different types of meridians including principal, divergent, tendinomuscular, and extraordinary. For the purposes of this article, we will only be evaluating the principal meridians.

How Many Acupuncture Meridians Are There?

There are twelve primary meridians, and each is associated with an organ of the body. The meridians are organized into “sister pairs.” Each pair contains a yin meridian and a yang meridian. Yin meridians are considered receptive, and yang meridians are considered expressive.

What Are The 12 Meridians of Acupuncture?

12 Primary acupuncture meridians travel over the entire body from the torso to the hands, from the hands to the face, from the face to the feet, and from the feet to the torso, and so on. This circulation ensures that Qi travels throughout the entire body. In addition, each meridian travels through its own organ as well as its sister organ. The cycle of Qi throughout the entire body is completed every 24 hours.

- Lung Meridian

- Large Intestine Meridian

- Stomach Meridian

- Spleen Meridian

- Heart Meridian

- Small Intestine Meridian

- Bladder Meridian

- Kidney Meridian

- Pericardium Meridian

- Triple Burner/San Jiao Meridian

- Gall Bladder Meridian

- Liver Meridian

How are meridians associated with organs?

As previously mentioned, each meridian is associated with one of the body’s organs. However, the concept of “organ” in the context of Chinese medicine is extremely different than that of allopathic medicine. With this in mind, it is important to recognize that stagnation of Qi in the Liver meridian does not necessarily indicate a Liver dysfunction in the context of western medicine. It is important to approach the concept of “organ” from a completely new perspective and with a beginner’s mind.

The primary meridians and organs are mated in Yin and Yang pairs:

Yin Meridians/Organs

- Lung

- Spleen

- Heart

- Kidney

- Liver

- Pericardium

Yang Meridians/Organs

- Large Intestine

- Stomach

- Small Intestine

- Bladder

- Gall Bladder

- Triple Burner/San Jiao

Many of these organs may seem fairly straight forward such as Lung, Heart, Kidneys, etc. However, the definitions of the medical functions of each organ in Chinese medicine vary considerably from how they are defined in allopathic medicine. A complete discussion of the philosophy behind the functions of each organ and the organs themselves would be too lengthy for this article. However, the two organs that may seem most unfamiliar are the Pericardium and the San Jiao.

Vital Organs in Chinese Medicine: Pericardium and San Jiao

The pericardium in allopathic medicine is a sack that merely encloses the heart. In Chinese medicine, the Pericardium is just as important as the Heart itself. For this reason it has its own meridian and its own functions. On the other hand, the San Jiao has no direct correlation with an organ in allopathic medicine, and this fact may make this organ just as mysterious as the concept of Qi to some people. However, the San Jiao is responsible for regulating the temperature, fluids, and environment of the chest (Upper Jiao), abdomen (Middle Jiao), and lower abdomen (Lower Jiao).

The concepts of Qi and Meridians are just a start to understanding the terminology of your acupuncturist. The philosophy and practice of Chinese medicine has developed over the course of 3,000 years in China and is deeply rooted in its culture. It is essential for those who are less familiar with Chinese medicine to feel empowered to partner with their acupuncturist to learn more about it and how to improve their overall health and wellness through a different, albeit just as important, medical practice.

About the Author

As a practitioner and healer in Washington, DC for more than a decade, I take a patient-centered approach to care through acupuncture, cupping, herbal medicines, and mind-body coaching, with a specialty in full-spectrum reproductive health care.